Effective Training, Athletic Efficiency & Performance Capacity

If you’re an athlete wanting to perform at your best on the sporting field, or you’re working with an athlete, it’s essential that you understand the athlete’s limitations. Performance means to carry out an action efficiently, so if you do not recognize the inefficiencies, there will be a limit on the athlete’s capacity to improve.

Imagine taking your car to a mechanic for a service because you want the engine to run more efficiently, and they replace the wiper blades & light bulbs, install new brakes, and wash the car for you, but they haven’t changed the air filter or replaced the spark plugs & oil (necessary for healthy engine function). All of that time & money wasn’t invested on the problem, and now, the car will run the exact same as it did before the service.

This seems obvious, but what is less clear for therapists, coaches and athletes is ‘what’ to work on & then ‘how’ to work on it.

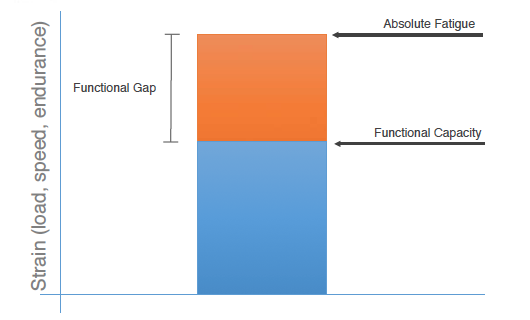

Firstly, let me explain the concept of Functional Capacity v.s. Functional Gap, and the benefits for an athlete that can avoid time spent in the Functional Gap and increase their Functional Capacity. Our ideal locomotor/movement system has its capacity or threshold. This means that our ability to maintain ideal “form”, which includes (and is not limited to) spinal length, joint centration, and quality intra-abdominal pressure (IAP), is inhibited when this Functional Capacity is exceeded. It is exceeded due to an increase in strain on the system, which is associated with increased load, speed or endurance. When this threshold is exceeded you enter into the Functional Gap, which lies between your Functional Capacity and Absolute Fatigue (see image).

Image from The Prague School Of Rehabilitation, Exercise Course Presentation

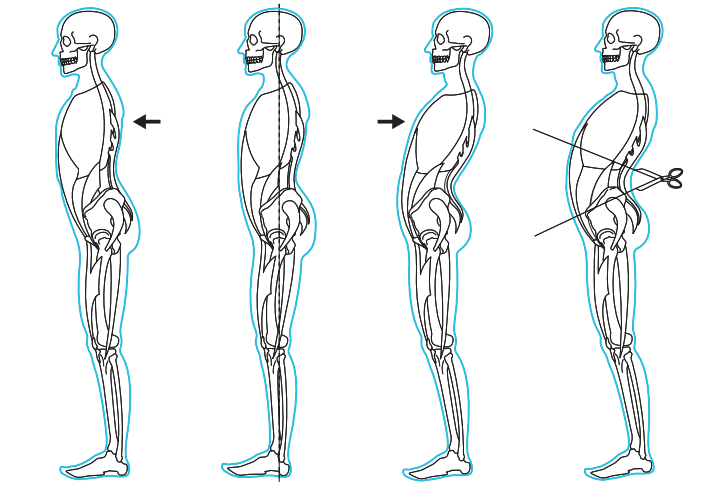

For example, an AFL footballer at their maximum sprinting capability, or at extreme fatigue towards the end of the 3rd or 4th quarters, may start to enter the Functional Gap, where the quality of their movement & optimal stabilization is reduced, and as a consequence, performance efficiency decreases and they’re at a higher risk of injury. They’re at increased risk of injury because the athlete will adopt a more primitive stabilizing strategy, such as hyperextension of the spine, elevated rib cage and anterior pelvic tilt, referred to as “open scissor” posture (see image). With this understanding, the most effective strategy for improving an athlete’s performance & reducing their injury risk is to increase their Functional Capacity, increase the time till Absolute Fatigue, and reduce the time spent in the Functional Gap.

Image from You See You Want, Standing Posture Assessment, https://iptnpt.tistory.com/230

Secondly, assuming we now know ‘what’ to do, ‘how’ do we do it? What system do we use for identifying the athlete’s limitations, and then improve their Functional Capacity? Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilisation (DNS) is an exercise rehabilitation approach, which focuses on restoring ideal breathing, core stabilization, neutral joint position, good quality support, and movement coordination & muscle timing, in order to restore full function and thus, improve performance.

For therapists or coaches that are assessing an athlete, this system helps to identify the athlete’s poor or non-preferred global stabilizing strategies (i.e. their gaps), and then you can use developmental positions/postures, which are fundamental to uprighting and locomotion, to change the athlete’s movement habit and fill those gaps you’ve identified. An important distinguishing feature of this approach is that we’re not targeting the muscle groups; rather, we’re creating a change at the brain and nervous system level, a new wiring.

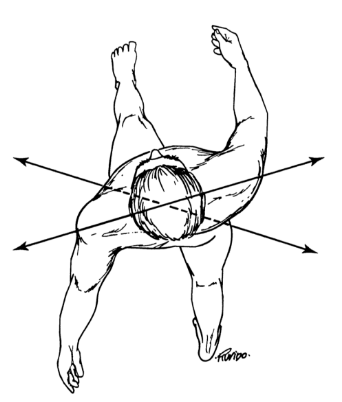

Image courtesy of Skilful Means, 2019 Athlete Development Retreat

Thirdly, you need the full investment of the athlete for his or her own improvement. This sounds obvious I know, but very often an athlete will enlist all of his or her trust in their coach for their improvement because it’s the coach that ‘knows’ best. This needs to change! The athlete needs to take full ownership of their perspective, their understanding, their training, and their growth. It’s possible, and in many cases, necessary for an athlete to evolve their perspective in order to uncover possibilities they didn’t previously consider possible, climb walls they thought were unclimbable, free themselves of prior conditioned beliefs and limits, discover themselves through movement and maximize their capacity to perform at their highest capability when required.

Just simply working harder than everyone else isn’t going to cut it. The athlete needs to be clear on what’s most important, what is of most value to them and their performance, and then invest their time on that. In regards to their movement pattern, the athlete needs to have a clear understanding of their old, non-preferred pattern, and then be able to feel & catch himself or herself when they resort back to that old habit. For example, the human body is a “turning” body. To prove my point, from a standing position, do the experiment where you take a step forward with your left foot and notice how your shoulder girdle is rotated to the left, and your pelvis to the right. Or in other words, the left shoulder and right hip joint are open, the right shoulder and left hip joint are closed. This means they’re reciprocal.

The ability to turn inside the corridor of your shoulders and pelvis is essential for optimising movement efficiency and performance, but it’s very often neglected in athletic training programs. If we cannot turn, we will undoubtedly shift our trunk in a frontal plane with everything we do, including walking, running & sprinting. Now if the athlete can’t feel such a shift, the shift will continue to happen at a great cost to their entire, global musculoskeletal system. This is where a coach or therapist ‘spotting’ their athlete is essential. It’s the ultimate accountability to minimise the old movement strategy and keep the athlete in ‘ideal’. In the image below, you can see the spotter gives their athlete a felt sense of what ‘ideal’ is, and with more repetitions, the ankle/foot biomechanics becomes smoother, more connected, and the athlete can start to ‘own’ the movement without the guidance of the hands.

Image courtesy of Skilful Means, 2019 Athlete Development Retreat

With time, the changes will become subconscious and the new habit will become more established. ‘Feeling’ and tuning into your body isn’t easy at first (especially if it’s new), but it’s essential for you to be able to own and make the changes in your movement, posture and stabilization to improve your overall efficiency and athletic performance. I use tools such as the Iron Edge Resistance Bands and Fighting Monkey 9-Speed Tool so that the athlete can collect feedback-rich information in real-time around how they’re organizing their movement, as well as enhance the athlete’s support/stepping function for increased connection, power, speed and overall output (see below).

Video courtesy of Skilful Means (2019)

Lastly, the developmental postures are generally slow, controlled movements that allow you to create a change because of their nature. If you move too quickly, you’ll miss where you’re compensating or escaping. These postures are to be used in conjunction with an athlete’s sport and skill development program with the intention to increase the loading without compromising the ideal movement and stabilizing strategy. Increasing the load on an athlete doesn’t mean heavier squats or deadlifts, but rather, increasing running intensity, jumping, landing, changing direction, coordination, or a combination of the above in a predictable and unpredictable setting. The developmental postures are directly correlated with the above movements, and the principles remain the same: Weight-shifting,... Length,... Quality Support,... Diaphragmatic Breathing,... IAP,... Relaxation,... Coordination & Timing,... and Joint Centration for ideal muscular coactivation. In doing so, we’re honouring ideal development, maturation of the nervous system, and locomotion. Successful rehabilitation is not simply a return to sport; it’s a return to sport with no observable, poor compensatory patterns, and the athlete has the confidence that they can out-perform. Not only is this essential for the athlete’s success right now, but also for the longevity of their body following their athletic career.

From this perspective, to increase an athlete’s efficiency and perform at their best, they need to take ownership for their improvement, identify their movement limitations with the guidance of a coach or therapist, influence the brain & nervous system to remove them, and then increase the training load whilst maintaining the ideal movement & stabilization pattern, and in doing so, build their Functional Capacity.